Each elementary particle has its own lifetime and mass. Electrons are thought to live essentially forever and have a mass of about 0.5 MeV. Protons, on the other hand, are believed to have a finite lifetime, but its length has not yet been measured; their mass is about 940 MeV. If we treat the electron’s mass as 0.5 g, the proton’s mass would correspond to roughly 940 g.

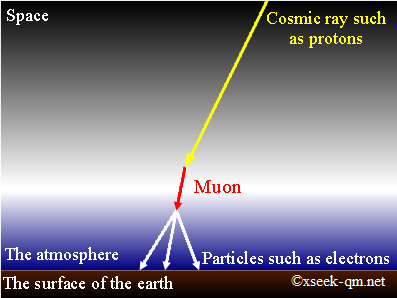

High‑speed protons roam through space; they are known as cosmic rays. When these protons strike atoms in the atmosphere, they generate many other particles, including taus and muons.

The tau lepton behaves much like an electron but has a mass of about 1800 MeV. With the electron set to 0.5 g, a tau would weigh about 1800 g. Its average lifetime is roughly 300 femtoseconds (1 fs = 1 quadrillionth of a second). Taus decay into electrons and neutrinos.

Muons also resemble electrons. A muon’s mass is about 100 MeV, or roughly 100 g in the everyday analogy. Its average lifetime is about 2 microseconds (1 μs = one‑millionth of a second). Scaling the tau lifetime to 1000 years would make the muon’s lifetime about 700 million years. Muons likewise decay into electrons and neutrinos.

Light travels about 600 m in 2 μs. Because a muon’s lifetime is also 2 μs, it should not be able to cover more than 600 m. Yet in reality muons travel over 6000 m and reach the ground. Special relativity explains this: time dilates for the fast‑moving muon, giving it more “proper time” before it decays.

| Particle | Mass | Lifetime |

|---|---|---|

| Electron | 0.5 MeV (0.5 g) | Infinite |

| Proton | 940 MeV (940 g) | Unknown |

| Tau | 1800 MeV (1800 g) | 300 fs (1000 years) |

| Muon | 100 MeV (100 g) | 2 μs (700 million years) |

That particles have finite lifetimes at all is striking. A candle’s life is set by the length of its wax, but a particle’s life is not pre‑assigned. A particle 1000 years old looks identical to one 700 million years old; in a sense, the particle has no memory of its age.

Each particle decays with a fixed probability per unit time. Imagine the particle “rolling a die” once every second:

The die is, of course, a metaphor. How does the particle actually “roll the die,” and how brief is the interval between rolls? I suspect that interval is exceedingly short—perhaps the smallest tick of time itself.

Clearly, much remains unknown about particle decay.

© 2002-2014 xseek-qm.net

広告