Derivation of two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin-1/2 from rotation of 3-sphere

Home > Quantum mechanics > Spin of quantum mechanics

2022/05/25

Published 2013/05/19

K. Sugiyama[1]

In this paper, we derive the two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin-1/2 from a rotation of 3-sphere.

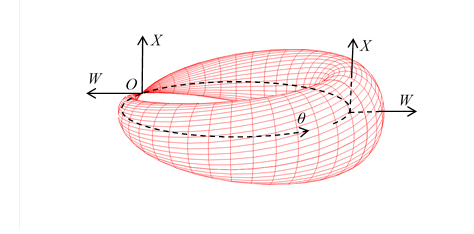

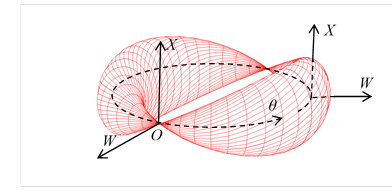

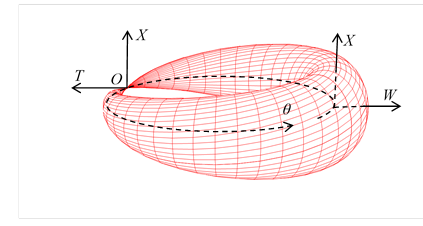

Figure 3-8: Wave function of spin-1/2 particle

The spin wave function changes its sign with a 360-degree rotation. Therefore, if one assumes the existence of an angle-dependent spin-1/2 wave function, the wave function takes on two different values at angles 0 and 360 degrees. This strange behavior is called "two-valuedness of spin-1/2." Due to this "two-valuedness of spin-1/2," it is believed that there is no angle-dependent spin-1/2 wave function.

To solve this mystery of "two-valuedness of spin-1/2" requires a revolution in the concept of the wave function. In the past, Kaluza and Klein interpreted the electromagnetic field function as a one-dimensional circle. Similarly, this paper interprets the wave function as a three-dimensional sphere.

|

|

|

This three-dimensional sphere is decomposed as follows.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The circle in the W-X plane in the above equation is shown in Figure 3-8. When the angle θ rotates 360 degrees, this circle is flipped over. This property is the true nature of "two-valuedness of spin-1/2."

CONTENTS

1.3.1 History of research of spin

1.3.2 History of research of manifold

1.4 New construction method of this paper

2 Confirmation of the traditional research of the spin

2.1 Pauli matrices and quaternion

2.2 Confirmation of the experiment of two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin

2.2.1 Verification of two-valuedness of the spin by experiment

2.2.2 Verification of angular momentum of the spin by an experiment

3 Derivation of the two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin

3.1 Derivation of the two-valuedness of spin

3.1.1 Consideration of 3-sphere

3.1.2 Taking a view of 2-sphere by the simultaneous sections method

3.1.3 Taking a view of 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method

3.1.4 Taking a view of 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method (The other way)

3.1.5 Even torus and odd torus

3.2 Derivation of angular momentum of spin

3.2.1 Construction of 1-dimensional helical space

3.2.2 Construction of 2-dimensional helical space

3.2.3 Construction of 3-dimensional helical space

3.2.4 Consideration of 3-dimensional helical space

1 Introduction

1.1 Subject

Kaluza and Klein introduced a one-dimensional sphere in extra-dimensional space to unify gravitational and electromagnetic forces. In this paper, we introduce a three-dimensional sphere in extra-dimensional space to derive the two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin-1/2.

1.2 Importance of Subject

Many researchers have attempted to quantize gravity, but without success. This quantization of gravity has become an important issue in physics. One way to quantize gravity was to interpret a point particle as a string, a one-dimensional manifold. Therefore, it can be inferred that interpreting the wave function of spin as a manifold is an effective way to quantize gravity.

1.3 History of research

1.3.1 History of research of spin

George Eugene Uhlenbeck and Samuel Abraham Goudsmit discovered the spin of the electron in 1925. Wolfgang Pauli formulated the spin by the Pauli matrices in 1927. Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac derived the spin by the Dirac equation in 1928.

1.3.2 History of research of manifold

Albert Einstein constructed the general theory of relativity by the 4-dimensional Riemann manifold in 1916. Theodor Kaluza[2] and Oskar Klein[3] constructed proposed in the Kaluza-Klein theory by the 1-dimensional circle in 1926.

1.4 New construction method of this paper

2 Confirmation of the traditional research of the spin

2.1 Pauli matrices and quaternion

In order to express the spin, Pauli defined the following Pauli matrices in 1927.

|

|

(2.1) |

|

|

(2.2) |

|

|

(2.3) |

|

|

(2.4) |

The products are shown below.

|

|

(2.5) |

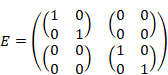

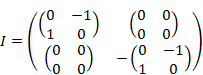

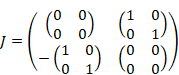

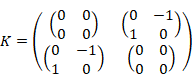

We define the unit quaternions by this Pauli matrices.

(Unit quaternions)

|

|

(2.6) |

|

|

(2.7) |

|

|

(2.8) |

|

|

(2.9) |

The products are shown below.

|

|

(2.10) |

These are the matrix representations of the following unit quaternions.

|

|

(2.11) |

William Rowan Hamilton discovered the unit quaternions in 1843.

2.2 Confirmation of the experiment of two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin

2.2.1 Verification of two-valuedness of the spin by experiment

H. Rauch[4] and S. A. Werner[5] verified the two-valuedness of the spin by the Neutron Interference Experiment in 1975. In this section, we confirm the two-valuedness of the spin.

We can express the wave function of a particle rotating about the z-axis by the Pauli matrices as follows.

|

|

(2.12) |

The rotating the angle of the rotation θ by 360 degrees does not bring it back to the same state, but to the state with the opposite phase. The rotating the angle of the rotation θ by 720 degrees brings it back to the original state.

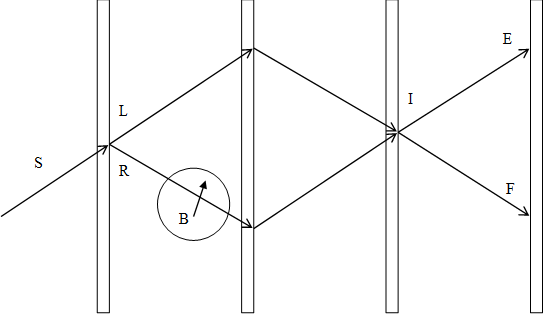

Figure 2-1: Experiment for verification of two-valuedness of spin

We divide Neutron to path L and path

R. Neutron of the path L goes through a domain without magnetic

field. Neutron of the path R goes through a domain with magnetic field.

As a result, the magnetic field changes the phase of the neutron of path R.

Quantity of the change of the phase ![]() is as follows.

is as follows.

|

|

(2.13) |

|

|

(2.14) |

Here, the variable ω is the angular frequency of precession of the spin of the neutron. The variable T is the time neutron passes through the magnetic field. The variable gn is a g-factor. Constant e is the elementary charge. Variable B is the strength of the magnetic field. Variable m is the mass of the neutron.

The neutron that passed along the path L and path R joins at the position I. We can observe it at position E or position F.

Since superposition of a wave function occurs when it joins at position E or position F, we can observe the phase shift. The phase shift was observed as the result of the experiment actually.

It has been clarified that a spin has two-valuedness by this experiment.

2.2.2 Verification of angular momentum of the spin by an experiment

Albert Einstein and Wander Johannes de Haas[6] verified the angular momentum of the spin by the following experiment in 1915.

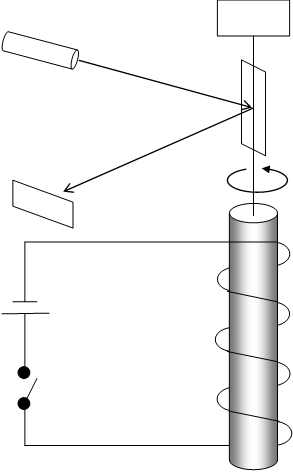

Figure 2-2: The experiment to verify the angular momentum of the spin

The experiment was performed as follows.

We apply the magnetic field to the disk of the magnetic material. Then, we make the disk stationary state. After that, we stop the magnetic field. Then disk begins to turn around. This effect is called "Einstein-de Haas effect." It has been clarified that a spin has angular momentum by this experiment.

3 Derivation of the two-valuedness and angular momentum of spin

3.1 Derivation of the two-valuedness of spin

The point particle cannot rotate, because the point particle has the radius of rotation zero. We need infinite momentum to get finite angular momentum by the radius of rotation zero.

We can express angular momentum L by using the radius r and momentum p as follows. The operator × is outer product.

|

|

(3.1) |

If L is finite and radius r is zero, momentum p becomes infinite.

On the other hand, we cannot derive the two-valuedness of the spin by a rotation of 2-dimensional surface of a sphere (2-sphere). Therefore, we consider the rotation of 3-dimensional surface of a sphere (3-sphere).

3.1.1 Consideration of 3-sphere

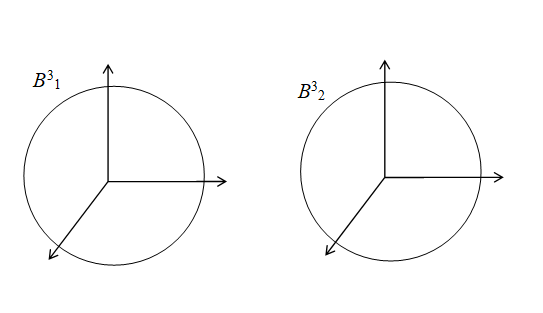

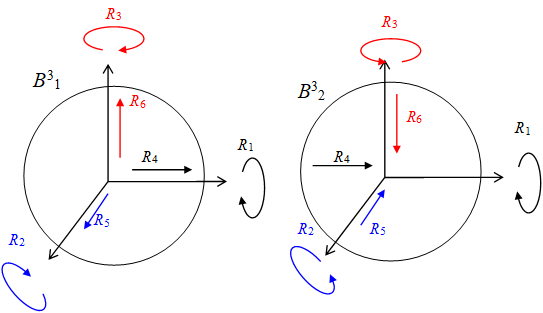

We can express 3-sphere S3 by combining two 3-dimensional solid sphere B31 and B32 in the following figure.

Figure 3-1: 3-sphere

3-sphere has 6 kinds of spin R1, R2, R3, R4, R5, and R6 like the following figure.

Figure 3-2: Rotation of 3-sphere

It is not difficult to consider the spin R1, R2, R3. However, it is difficult to consider spin R4, R5, R6.

It is difficult to consider 3-sphere because the 3-sphere exists in the 4-dimensional space. Then, we try to consider the 3-sphere by taking a view of two sections of 3-sphere simultaneously. We call the method to take a view of the two sections simultaneously like this the simultaneous sections method.

First, we try to apply the simultaneous sections method to 2-sphere because it is easier to consider 2-sphere than 3-sphere.

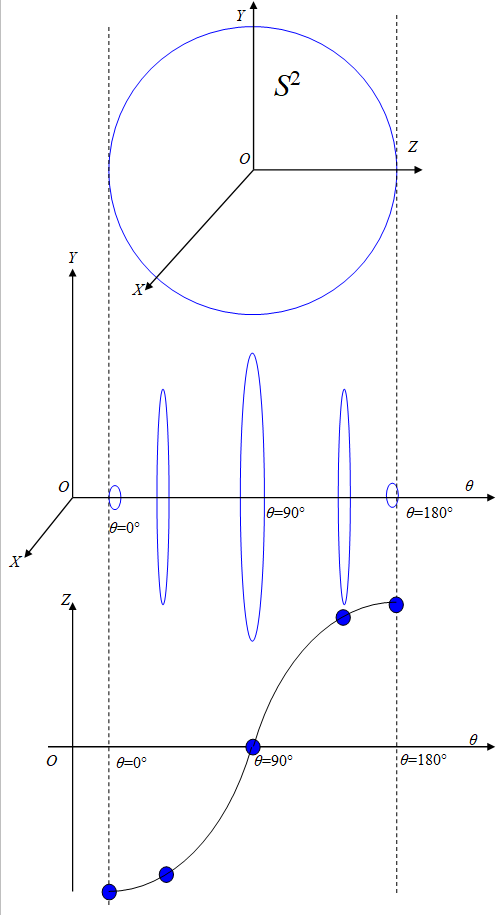

3.1.2 Taking a view of 2-sphere by the simultaneous sections method

We suppose that 2-sphere S2 in extra 3-dimensional space specified by the coordinates (X, Y, Z). If the radius of the 2-sphere is 1, 2-sphere satisfies the following equation.

|

|

(3.2) |

We can express this sphere by a sectional view of X-Y plane and the position on the Z-axis.

|

|

(3.3) |

|

|

(3.4) |

Here, angle θ satisfies the following equation.

|

|

(3.5) |

We show the 2-sphere that is applied the simultaneous sections method to in the following figure.

Figure 3-3: The simultaneous sections of 2-sphere

We express the radius of the circle in the X-Y plane and position Z at the angle θ.

Table 3-1: The radius of the circle in the X-Y plane and position Z at the angle θ

|

Angle θ |

Radius of the circle in the X-Y plane |

Position Z |

|

0° |

0 |

-1 |

|

90° |

1 |

0 |

|

180° |

0 |

1 |

We can consider the structure of the 2-sphere by taking a view of the radius of the circle in the X-Y plane and position Z simultaneously, like this.

Then, we apply the simultaneous sections method to 3-sphere.

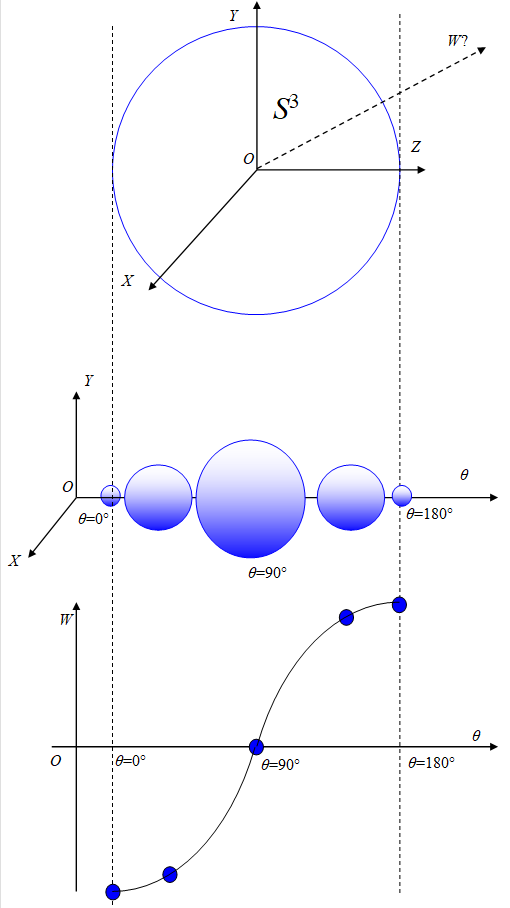

3.1.3 Taking a view of 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method

We suppose that 3-sphere S3 in 4-dimensional space specified by the coordinates (W,X,Y,Z). If the radius of the 3-sphere is 1, 3-sphere satisfies the following equation.

|

|

(3.6) |

We can express this sphere by a sectional view of X-Y-Z space and position on the W-axis.

|

|

(3.7) |

|

|

(3.8) |

We show the 3-sphere that is applied the simultaneous sections method to in the following figure.

Figure 3-4: The simultaneous sections of 3-sphere

We express the radius of the sphere in X-Y-Z space plane and position Z at the angle θ.

Table 3-2: The radius of the sphere in X-Y-Z space and position Z at the angle θ

|

Angle θ |

Radius of the sphere in X-Y-Z space |

Position Z |

|

0° |

0 |

-1 |

|

90° |

1 |

0 |

|

180° |

0 |

1 |

In this section, we divided 3-sphere to 2-sphere and position on an axis. However, we can divide 3-sphere by the other way, too. We consider the way in the next section.

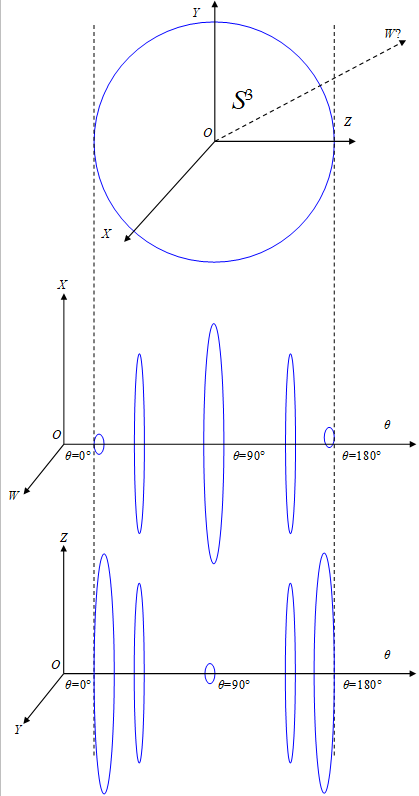

3.1.4 Taking a view of 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method (The other way)

We suppose that 3-sphere S3 in extra 4-dimensional space specified by the coordinates (W,X,Y,Z). If the radius of the 3-sphere is 1, 3-sphere satisfies the following equation.

|

|

(3.9) |

We can express this sphere by a sectional view of W-X plane and Y-Z plane.

|

|

(3.10) |

|

|

(3.11) |

This is the Hopf fibration which Heinz Hopf found in 1931.

We show the 3-sphere that is applied the simultaneous sections method to in the following figure.

Figure 3-5: The simultaneous sections of 3-sphere (The other way)

We express the radius of the circle in W-X plane and circle in the Y-Z plane at the angle θ.

Table 3-3: The radius of the circle in W-X plane and circle in the Y-Z plane at the angle θ

|

Angle θ |

Radius of the circle in W-X plane |

Radius of the circle in the Y-Z plane |

|

0° |

0 |

1 |

|

90° |

1 |

0 |

|

180° |

0 |

1 |

Here we can connect the circle in the W-X plane at the angle θ = 0° and the circle in the W-X plane at the angle θ = 180° because they have the same radius 0. In addition, we can also connect the circle in the Y-Z plane at the angle θ = 0° and the circle in the Y-Z plane at the angle θ = 180° because they have the same radius 1.

Therefore, we can interpret the angle θ as an angle of rotation of the manifold.

This rotation turns the circle inside out. For example, the circle in the Y-Z plane is turned inside out at the angle of rotation θ = 180°. Therefore, this rotation is strange spin that is different from the normal spin.

We call the strange spin "toric spin." In addition, we call normal spin "spheric spin."

3.1.5 Even torus and odd torus

Here we express 3-sphere as follows.

|

|

(3.12) |

|

|

(3.13) |

We express the 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method in the following figure.

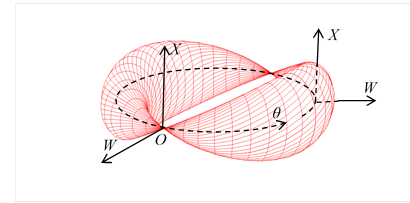

Figure 3-6: Wave function of spin-1 particle(W-X-θ)

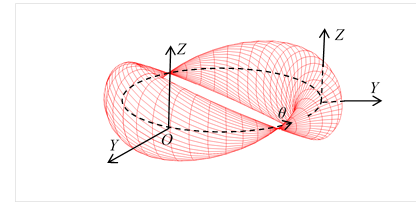

Figure 3-7: Wave function of spin-1 particle(Y-Z-θ)

We can interpret the above torus as a wave function of spin-1 particle. We can express it by the complex function as follows.

|

|

(3.14) |

Next, we express 3-sphere as follows.

|

|

(3.15) |

|

|

(3.16) |

We can express the 3-sphere by the simultaneous sections method in the following figure.

Figure 3-8: Wave function of spin-1/2 particle (W-X-θ)

Figure 3-9: Wave function of spin-1/2 particle (Y-Z-θ)

We can interpret the above torus as a wave function of spin-1/2 particle. We can express it by the complex function as follows.

|

|

(3.17) |

Here we express 3-sphere as follows.

|

|

(3.18) |

|

|

(3.19) |

Variable n is an integer. We call the torus that has even n even torus. We call the torus that has odd n odd torus.

3.2 Derivation of angular momentum of spin

In this paper, we interpret spin as a rotation of 3-sphere. Why does the rotation of 3-sphere have the same angular momentum as the angular momentum in the 3-dimensional normal space.

In this section, we consider the possibility that the 3-sphere connects to the 3-dimensional normal space.

3.2.1 Construction of 1-dimensional helical space

We can construct 1-dimensional helical space as follows.

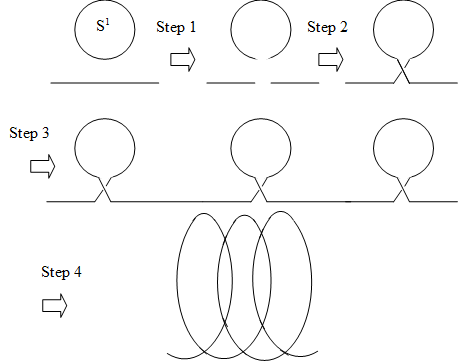

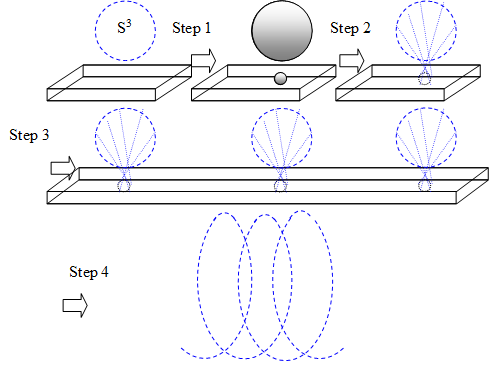

Figure 3-10: Construction of 1-dimensional helical space

We explain the transformation of each step in the following table.

Table 3-4: Construction of 1-dimensional helical space

|

Step |

Method of construction |

|

|

1 |

If we remove one point from a circle, we can get an arc. On the other hand, if we remove one point from a segment of a line, we can get two boundaries. |

|

|

2 |

We connect their boundaries. |

|

|

3 |

If we repeat this process, we can connect many circles. |

|

|

4 |

If we change the orientation of the circle, we can construct 1-dimensional helical space. |

|

We can express 1-dimensional helical space of the matrix representations of complex numbers as follows.

|

|

(3.20) |

The variables T and X are the coordinates of an extra space. The variable R is a radius of the extra space. The variable Θ is the angle in the extra space.

The symbols {E, I} are matrix representations of complex numbers.

|

|

(3.21) |

|

|

(3.22) |

|

|

(3.23) |

We express the coordinate x of a normal space by a wavelength λ as follows.

|

|

(3.24) |

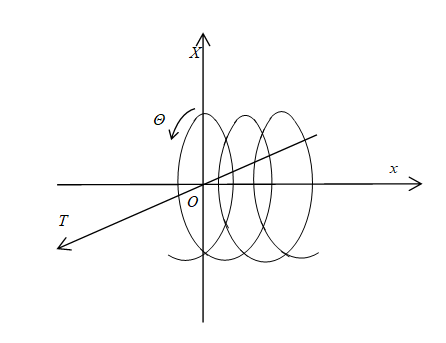

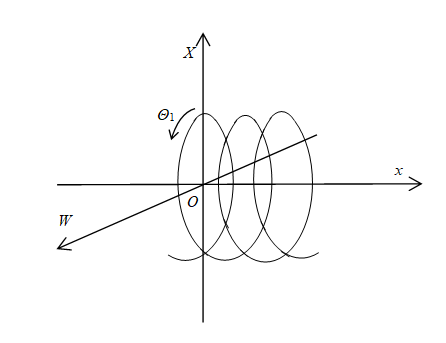

Figure 3-11: 1-dimensional helical space

If we combine the both ends, we can get 1-dimensional helical circle.

|

|

(3.25) |

|

|

(3.26) |

Here, n is an integer. The variable Θ is the angle of rotation of the major radius of helical circle. The variable r is the major radius of helical circle. The variable R is the minor radius of helical circle. The variables {W, X} are coordinates of an extra space. The variables x are coordinates of a normal space.

We express the 1-dimensional helical circle in the following figure.

Figure 3-12: 1-dimensional helical circle

Is it possible to do the same thing in 2-dimensional space? We consider it in the next section.

3.2.2 Construction of 2-dimensional helical space

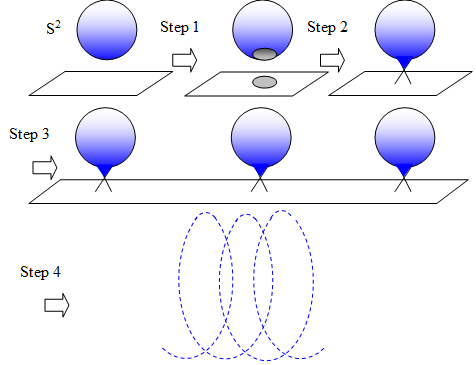

We can construct 2-dimensional helical space as follows.

Figure 3-13: Construction of 2-dimensional helical space

We explain the transformation of each step in the following table.

Table 3-5: Construction of 2-dimensional helical space

|

Step |

Method of construction |

|

|

1 |

If we remove one point from a 2-sphere, we can get 2-dimensional disk. On the other hand, if we remove one point from a plane, we can get a boundary like a circle. |

|

|

2 |

We connect their boundaries. |

|

|

3 |

If we repeat this process, we can connect many 2-sphere. |

|

|

4 |

If we change the orientation of the 2-sphere, we can construct 2-dimensional helical space. |

|

We cannot express 2-dimensional helical space by the trigonometric functions. We cannot express 2-dimensional helical space by the complex function, too. Therefore, I do not guess 2-dimensional helical space exists. However, 3- dimensional helical space might exist. We consider it in the next section.

3.2.3 Construction of 3-dimensional helical space

We can construct 3-dimensional helical space as follows.

Figure 3-14: Construction of 3-dimensional helical space

We explain the transformation of each step in the following table.

Table 3-6: Construction of 3-dimensional helical space

|

Step |

Method of construction |

|

|

1 |

If we remove one point from a 3-sphere, we can get 3-dimensional solid sphere. On the other hand, if we remove one point from 3-dimensional space, we can get a boundary like 2-sphere. |

|

|

2 |

We connect their boundaries. |

|

|

3 |

If we repeat this process, we can connect many 3-sphere. |

|

|

4 |

If we change the orientation of the 3-sphere, we can construct 3-dimensional helical space. |

|

We can express 3-dimensional helical space of the matrix representations {E, I, J, K} of unit quaternions as follows.

|

|

(3.27) |

The variables {W, X, Y, Z} are coordinates of an extra space. {Θ1, Θ2, Θ3} are the angle in the extra space. R is a radius of extra space.

The matrix representations {E, I, J, K} of unit quaternions are shown below.

|

|

(3.28) |

|

|

(3.29) |

|

|

(3.30) |

|

|

(3.31) |

|

|

(3.32) |

We express the coordinate (x, y, z) of the normal space by the wavelength {λ1, λ2, λ3} as follows.

|

|

(3.33) |

|

|

(3.34) |

|

|

(3.35) |

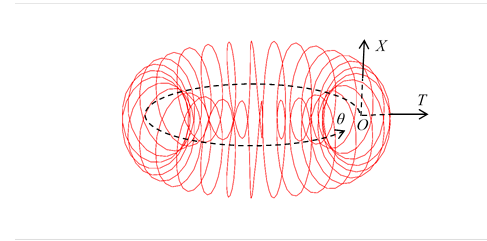

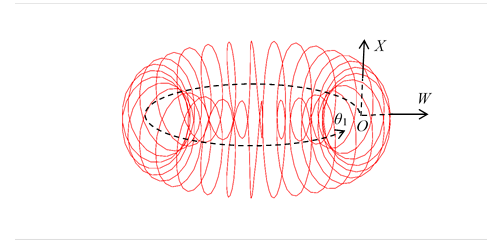

Figure 3-15: 3-dimensional helical space

If we combine the both ends, we can obtain 3-dimensional helical sphere.

|

|

(3.36) |

|

|

(3.37) |

|

|

(3.38) |

|

|

(3.39) |

Here, {n1, n2, n3} are integers. {Θ1, Θ2, Θ3} are the angles of rotation of the major radius of helical circle. The variable r is the major radius of helical circle. The variable R is the minor radius of helical circle. The variables {x, y, z} are the coordinates of normal space.

We can express the 3-dimensional helical sphere symbolically in the following figure.

Figure 3-16: 3-dimensional helical sphere

3.2.4 Consideration of 3-dimensional helical space

1-dimensional helical space corresponded to complex. On the other hand, 3-dimensional helical space corresponded to quaternions. I guess 2-dimensional helical space does not exist because triples of numbers do not exist.

We can interpret a position in 3-dimensional helical sphere as the position in normal 3-dimensional space. Therefore, we can interpret an angular momentum in 3-dimensional helical sphere as an angular momentum in normal 3-dimensional space. In other words, we can interpret the spin of the quantum mechanics as the rotation of a particle.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we derived the following property of the spin.

(1) Two-valuedness of a spin

(2) Angular momentum of a spin

5 Future Issues

Future issues are shown as follows.

- Derivation of Dirac equation

6 Supplement

6.1 Spin of 3-sphere

We introduced the 3-sphere as the wave function in 3-space in this paper.

We express the 3-sphere by the quaternionic functions as follows.

|

|

(6.1) |

|

|

(6.2) |

|

|

(6.3) |

|

|

(6.4) |

|

|

(6.5) |

|

|

(6.6) |

This is the Hopf fibration.

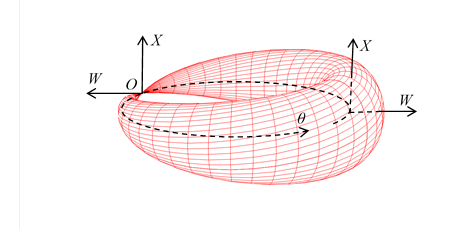

We express the coordinate (W, X) for the rotational angle θ in the following figure.

Figure 6-1: Wave function of the particle of spin 1

The value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 180 degrees becomes the (-1) times of the value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 0 degrees.

|

|

(6.7) |

The value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 360 degrees becomes the same value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 0 degrees.

|

|

(6.8) |

We interpret the manifold as the wave function of a particle of spin 1. We interpret the rotational angle of the manifold as the phase of the wave function. We interpret the surface area of the manifold as the absolute value of the wave function.

Here we change the angle θ to the half angle.

|

|

(6.9) |

Then, we express the quaternionic function as follows.

|

|

(6.10) |

|

|

(6.11) |

|

|

(6.12) |

|

|

(6.13) |

|

|

(6.14) |

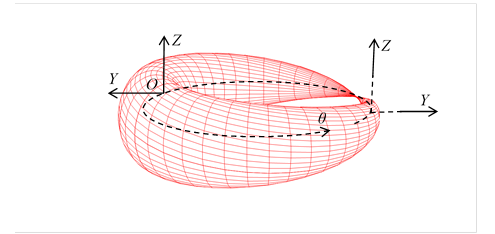

We express the coordinate (W, X ) for the rotational angle θ in the following figure.

Figure 6-2: Wave function of a particle of spin 1/2

The value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 360 degrees becomes the (-1) times of the value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 0 degrees.

|

|

(6.15) |

The value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 720 degrees becomes the same value of the quaternionic function f of the rotational angle 0 degrees.

|

|

(6.16) |

We interpret the manifold as the wave function of a particle of spin 1/2. We interpret the rotational angle of the manifold as the phase of the wave function. We interpret the surface area of the manifold as the absolute value of the wave function.

7 Appendix

7.1 Arrangement of Terms

Table 7-1: Spin and so on

|

# |

Term |

Explanation |

|

1 |

Spin |

Rotation of the object that contains the axis of rotation. |

|

2 |

Spheric spin |

Rotation that does not include the inside out circle. |

|

3 |

Toric spin |

Rotation, including the inside out circle. |

Table 7-2: Helical space and so on

|

# |

Category |

Term |

|

1 |

Space |

Helical space |

|

2 |

Circle |

Helical circle |

|

3 |

Sphere |

Helical sphere |

8 Acknowledgment

In writing this paper, I thank from my heart to NS who gave valuable advice to me.